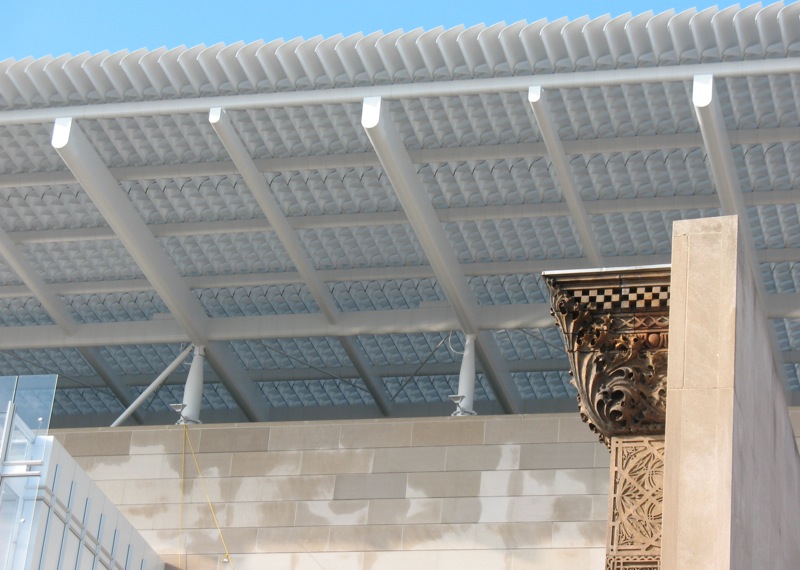

A glimpse inside the lobby of Renzo Piano's planned Kimbell Art Museum expansion. Rendering by Renzo Piano Building Workshop.

Here’s a question for you: What do Amsterdam, Atlanta, Basel, Bern, Chicago, Dallas, Houston, Los Angeles and San Francisco all have in common?

Answer: The presence of a McDonald’s, a Burger King, and a museum designed by the architect Renzo Piano.

With additional Piano museums completed in such Burger King-deprived corners of the world as Paris, France, and Noumea, New Caledonia, along with Japanese airports and Manhattan skyscrapers and countless under-construction projects rising around the globe, the architect’s office should be ready to put up at least a “millions served” sign. While such ambitious business expansion might initially seem like an unusual feat for an architect who is also widely acclaimed at an artistic level, his success was rooted in the simple economics of the recent worldwide demand for big-budget museums built to increase their cities’ tourist revenue. Although Piano’s work is subtler thana some of the trend’s most outrageous advances, from Frank Gehry’s visual explorations at the Guggenheim Bilbao to the uncharted new ethical territory now being breached by Tod Williams and Billie Tsien’s planned Barnes Foundation expansion, the Italian architect’s worldwide expansion inspires a similar level of awe in its own way.

Renzo Piano's mammoth extension to the Art Institute of Chicago. Photo credit: happy_stomach

The city of Fort Worth, Texas, however, seems destined to become one of Piano empire’s most difficult conquests. The designer’s scheme for an addition to the Kimbell Art Museum, unveiled yesterday, must attempt to apply the contemporary art world’s commercial demands to the work of an architect who resisted such material temptations with an almost religious level of conviction. Much to the dismay of his few customers, Kimbell designer (and former Piano employer) Louis I. Kahn operated, at a certain level, without regard for the particular specifics of what his clients wanted, or even for what his personal instincts as a designer suggested. Instead, he considered his architecture to be a search for the elusive essence of what, in his words, the building “wanted to be.” What was the basic, essential character of a school, or a church, or an art museum? His pursuit of an answer was always exhaustive, conducted through a design process that involved drawing up and rejecting scores of different schemes for each project before finding a balance that he felt was right.

In Ft. Worth, Kahn’s process resulted in a museum design which revolved around the singular purpose of creating optimal conditions for the perception of art. The building appears at first glance to be a simple row of ground-hugging vaults, modest in comparison to most recent cultural projects:

Photo credit: Diorama Sky

What the Kimbell lacks in exterior spectacle, however, it makes up for with its functional effectiveness. The museum’s one-story design enables it to take maximum advantage of the strong Texas sun, using natural light from above to more accurately render the colors in its displays of artwork. Sophisticated light deflectors, which the architect referred to as “daylight fixtures,” shelter the collection from the sun’s damaging side effects and glare.

Photo credit: Xavier de Jauréguiberry

Kahn’s mastery of daylighting, along with the museum’s intimate scale and careful attention to detail, resulted in the creation of a subtle shrine to the deliberate contemplation of art.

Photo credit: ApplePirate

What more could a cultural institution wish for? Tourist revenue and attention, perhaps. Where the Kimbell design was primarily concerned with displaying art, other landmark buildings before and since have placed emphasis on attracting visitors through their ticket lines in the first place. The Guggenheim museums in New York and Bilbao, for example, sought popular spectacle through their use of unusual curved forms, which stood out in contrast to their more traditional urban surroundings. The results still appear shocking today:

Frank Lloyd Wright's landmark Guggenheim Museum in New York. Photo credit: grytr

Frank Gehry's contemporary Guggenheim successor in Bilbao. Photo credit: disgustipado

Santiago Calatrava’s more recently completed Milwaukee Art Museum can even lure unsuspecting tourists with its motorized flapping wings:

After decades of watching larger and more extroverted buildings draw greater crowds, the Texas art museum directors understandably wanted to expand their institution’s capacity. The temptation would be familiar to anyone who has ever visited the drive-through window of one of the local fast food chains: “Would you like to supersize?”

The first time that they said “yes” was in 1989. As with yesterday’s proposal, that plan was inspired by a desire to better accommodate the crowds attracted by lucrative traveling exhibitions. The idea’s implementation, however, was crude; additional vaults would have simply been slapped onto each side of the Kimbell building, creating a chimera which critic Paul Goldberger described as “the architectural equivalent of a stretch limousine.” Vehement reactions from historic preservationists and Kahn’s relatives led the museum board to quickly pull their proposal.

Yesterday’s attempt took a more careful approach. Despite Piano’s prolific business success, design quality remains his primary objective; each of his projects is crafted with a subtle elegance and intense tectonic rigor likely inspired by his years spent working for Kahn. Piano’s diverse background will hopefully enable his interpretation of a Kimbell expansion to more effectively bridge the creative and commercial worlds.

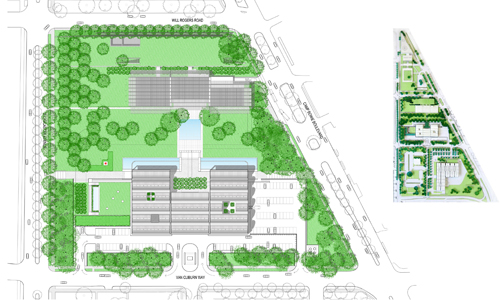

The site plan of the future Kimbell complex, by Renzo Piano Building Workshop.

In order to achieve that goal, Piano’s new building must shoulder the burden of the institution’s ambitious expansion program while also tiptoeing around the serenity of his former master’s original museum. The resulting compromise, to be erected above the original Kimbell’s location in the previous site plan, hides its commercial scale by burying significant portions of its mass underground:

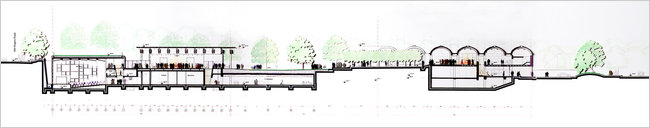

Section of the Kimbell expansion by Renzo Piano Building Workshop. Piano's new addition is on the left.

This move prevents the new building from overpowering the delicacy of its older predecessor, while also retaining some of the greenery of the original museum’s lawn as a gesture to the public. A look at Piano’s previous California Academy of Sciences project, however, reveals that the architect is also capable of envisioning more creative manipulations of a ground plane:

Photo credit: rossrenjilian

Although those grassy knolls were actually constructed on the roof of Piano’s California museum, not its ground level, the basic concept would have had interesting applications at the Kimbell. Slopes of earth could have been carved and stretched to create places to sit, perhaps in an effect similar to Maya Lin’s Wave Field, replacing the lost stretches of the old museum lawn. Where such an organic design might have posed a contemporary challenge to the Kimbell’s conservative styling, it would have done more to preserve the spiritual intentions of landscape architect Harriet Pattison’s current tranquil environment…

Photo credit: Dallas1200am

… than could likely be rescued in the wake of the glass and steel barge now slated to land there:

Rendering by Renzo Piano Building Workshop.

Although the new building’s axial alignment and fine details respect the old Kimbell’s proportions, the attempt is in danger of stepping a bit too far into the past; its stiff classical allusions and starched orthogonal lines could almost recall the monuments built by the Italian Fascists, or at least an Edward Durrell Stone building.

Other aspects of the new Kimbell are nicer. Piano at least keeps his creation a respectful distance away from Kahn’s work, 90 feet, although my gut reaction is that it should have been moved back even further. That placement will also supposedly bring more visitors to the Kimbell’s porches, which would support Kahn’s original intentions for the garden on the gloomy days when the excessive crowds don’t completely overrun it. In a world where every other museum aims to turn itself into a bustling circus, why not keep one good place to sit and think?

Ultimately, Piano seems to have tried his best to minimize the collateral damage of the aggressive program that he was given. Maybe the resulting museum will even has some positive effects if it liberates the old Kimbell from tourist loads that it wasn’t designed to handle. But ultimately, the situation reminds of a quote by the architect Cedric Price. As recounted by Lebbeus Woods, Price would ask his clients: “Do we really need this building?” If the new Kimbell is indeed necessary, then the public benefits provided by its spaces might even represent a continuation of the Athenian democratic values evoked by Kahn’s original museum. Otherwise, the Kimbell could go down in architectural history as an institution that fell for the kind of expansionist imperial hubris often associated with its first building’s Roman predecessors. We can only hope that Piano has been drawing with a very careful hand.